Power quality in research facilities is one of those topics that only gets attention after something goes wrong. A mass spectrometer reboots mid-run. A freezer alarm screams at 2 a.m. A laser controller logs a fault that nobody can reproduce. Surges and transients are frequent culprits in these “it just happened” events. They’re fast, often invisible to people on site and capable of quietly degrading electronics long before a dramatic failure shows up.

Research environments in Australia are uniquely exposed. University campuses and research precincts tend to have long distribution runs, multiple switchboards, and a mix of loads that change throughout the day. Facilities teams also have to support everything from wet labs and imaging suites to high-performance computing clusters and precision machining. Each of those systems can generate electrical disturbances, and sensitive instrumentation can be the first to complain.

This article unpacks what surges and transients are, why they matter so much for high-value lab equipment and how to build a protection approach that doesn’t rely on luck. The goal is not just to “install a device,” but to create a practical, layered plan that protects instruments, reduces downtime and supports repeatable science.

What Surges and Transients Really Are (and Why They're Common in Labs)

A surge or transient is a short-duration overvoltage event. The timescale can be microseconds to milliseconds. This means equipment can be impacted even if building lights never flicker. These events come from outside and inside your facility. External sources include lightning activity (even at a distance), switching on the utility network, faults on the feeder or automatic circuit recloser operations.

In Australia, lightning activity varies significantly by region. Northern Australia experiences some of the highest lightning flash densities in the world, whilst southern regions see more moderate activity. Even buildings in low-lightning areas can be affected by switching events on the distribution network.

Internal sources include switching large inductive loads such as motors and pumps, variable speed drives, lift or HVAC switching, transformer energisation and capacitor bank switching.

Research sites often have more internal switching activity than typical offices. Chillers cycle, vacuum pumps kick on and off, autoclaves heat up and mechanical plant loads shift as labs change occupancy and setpoints. Each switching action can create a transient that propagates through the electrical system.

Power quality in research facilities gets complicated quickly when sensitive instruments share distribution with “noisy” loads. Even if a transient doesn’t cause an immediate crash, repeated exposure can accelerate wear in power supplies and input protection circuits. This increases the risk of premature failure.

Why Expensive Instrumentation Is Vulnerable

Many high-end instruments contain precision sensors, high-speed electronics and tightly regulated internal rails. They may also have strict uptime requirements due to long runs or sample stability. Common vulnerabilities include the following.

Fragile electronics and control boards. Modern instruments rely on microcontrollers, field-programmable logic and switching power supplies. Transients can stress semiconductors, degrade capacitors over time and cause nuisance resets.

Calibration and data integrity risks. A transient might not destroy anything, yet it can interrupt a run, corrupt a data file or create subtle measurement anomalies. These are the worst failures because they waste time without leaving a clear forensic trail.

Interconnected systems multiply the risk. Instruments rarely operate alone. They connect to PCs, network switches, pumps, chillers, PLCs and building management systems. A transient can travel through power lines but it can also ride in via data lines and shared earth references.

Downtime costs are outsized. A single interruption can mean lost samples, missed project timelines, rescheduled imaging sessions and staff time spent troubleshooting. The true cost often exceeds the replacement cost of a component.

A Layered Protection Strategy That Actually Works

No single device can “solve” surge and transient risk. The most reliable approach is layered, coordinated and designed around where energy enters the site and how it moves through the distribution network.

Step 1: Start With Coordinated Surge Protection Devices (SPDs)

SPDs are designed to clamp transient voltages and divert surge energy safely to earth. The key is coordination across multiple points.

At the main switchboard or service entrance: This layer deals with large, external surge energy and reduces what gets into the building.

At distribution boards feeding lab areas: This reduces residual surges and protects downstream circuits.

At point-of-use (near critical instruments): This provides final-stage protection where sensitive loads connect.

Coordination matters. If only point-of-use devices exist, they can be overwhelmed by larger events. If only an upstream device exists, residual transients can still reach sensitive equipment, especially on long cable runs.

Step 2: Treat Earthing and Bonding as Part of Protection, Not a Separate Topic

SPDs are only as effective as the path to earth. Poor bonding or high-impedance earth paths can leave clamp voltages higher than expected. Practical actions include verifying earth continuity, ensuring equipotential bonding in lab zones and checking that shielding and metallic services are correctly bonded where required.

Power quality in research facilities often improves dramatically after basic earthing and bonding issues are corrected, especially in older buildings with layers of additions and renovations. Australian installations must comply with AS 3000 (Wiring Rules), which sets out earthing and bonding requirements for electrical installations.

Step 3: Use Zoning to Keep ``Noisy`` Loads Away From Critical Instruments

Electrical zoning reduces the coupling between disturbance sources and sensitive loads. This can look like dedicated circuits for key instruments, separate distribution for plant rooms or strategic placement of lab boards. The goal is to ensure that large cycling loads do not share the same upstream impedance as instrumentation circuits.

Step 4: Add Ride-Through Where Resets Are Unacceptable

Surge protection reduces overvoltage stress, yet it does not provide continuity during voltage dips or momentary interruptions. Some instruments are more sensitive to brief sags than to transients. A correctly sized UPS or a power conditioner designed for short ride-through, can prevent nuisance resets and protect ongoing runs.

Step 5: Protect Data and Signal Pathways Too

Instrument damage and faults do not always enter via mains power. Network lines, USB connections, and signal cables can conduct transient energy between systems. A protection plan should consider surge-rated protection for data lines where appropriate, along with good cable management and grounding practices for shields.

Maintenance and Verification: The Step Most Facilities Miss

SPDs are not “set and forget.” Many devices show status indicators, yet those indicators do not always tell the full story of cumulative wear. Periodic inspection, thermal checks at boards and scheduled verification help ensure protection remains active.

More importantly, verification should include evidence. When an event occurs, it helps to know what happened, where it entered and whether protective layers operated as intended. That is where monitoring becomes the difference between guesswork and confident action.

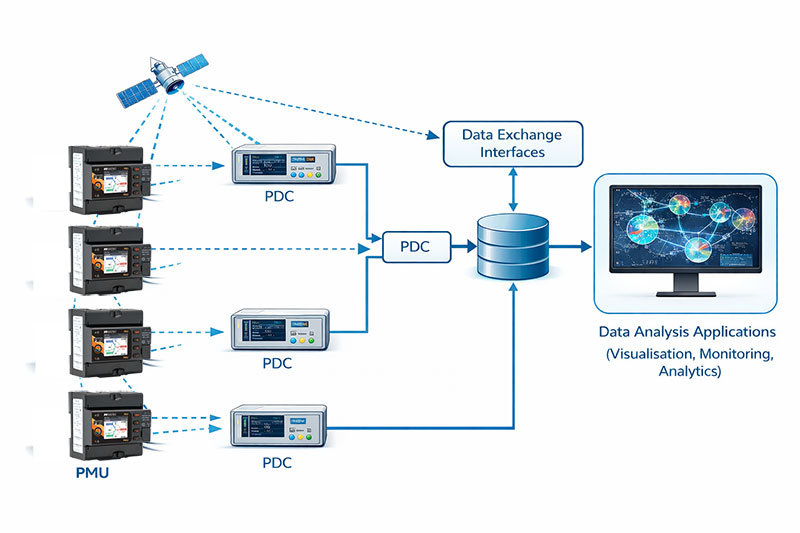

How SATEC Supports the Metering Solution for Research Facilities

Surge protection is strongest when it is paired with visibility. Power quality in research facilities improves faster when teams can see events, correlate them with equipment faults and prove whether changes reduced risk.

SATEC’s energy metering and power quality monitoring products are designed to provide that visibility. By placing meters at the right points in the electrical hierarchy, such as incoming supply, key distribution boards and critical lab feeders, facilities teams can capture and trend power quality performance. This includes events that align with instrument trips or unexplained alarms. This supports faster troubleshooting and helps separate upstream network issues from on-site switching events.

Our meters can also feed a monitoring layer through Expertpower cloud software. This enables centralised viewing, reporting and ongoing performance tracking across the site. That combination is especially useful in research environments where different buildings and lab zones have very different load profiles.

A structured metering approach helps you validate the impact of changes such as new SPDs, altered zoning, plant upgrades or added Uninterruptible Power Supply (UPS) systems. It also creates a common language between facilities, lab managers and service contractors: time-stamped evidence rather than opinions.

A practical way to frame it is simple: surge and transient protection reduces exposure and metering confirms results. When both are in place, investment decisions become easier to justify and recurring issues become easier to eliminate.

Pulling It Together Without Over-Engineering It

Surges and transients are part of modern electrical systems and research sites are full of both sensitive loads and disturbance sources. A strong approach blends coordinated SPDs, sound earthing and bonding, sensible zoning and ride-through where resets are costly. Monitoring closes the loop by confirming what is happening and whether improvements are working.

Power quality in research facilities is not just an engineering concern. It is operational risk management for science. Protect the instruments, protect the data and give your teams the insight to keep experiments running even when the electrical environment gets messy.

Get in touch with our power quality team of experts today.

FAQs - Power Quality in Research Facilities: Surge and Transient Protection for Expensive Instrumentation

What’s the difference between a surge and a transient?

Both are short-duration overvoltage events; “transient” is often used as the broader term, while “surge” commonly refers to higher-energy events that SPDs are designed to clamp and divert safely.

Will an Uninterruptible Power Supply (UPS) protect my instruments from surges and transients?

A UPS can help with ride-through during dips and brief outages but it shouldn’t be your only defence against surges. Coordinated surge protection (SPDs) at boards and near critical loads is still important.

Where should surge protection be installed in a research facility?

Best practice is a layered approach: at the main switchboard, at distribution boards feeding lab areas and near the most sensitive or expensive instruments for final-stage protection.

How does metering help with surge and transient protection?

Power quality monitoring shows when events occur and where they’re entering, helping you correlate instrument faults with electrical disturbances and verify whether protection upgrades are actually reducing incidents.